The title of this article alludes to two recent articles that attempt to capture the dire contemporary condition of urban Glasgow. It aims to provide an antidote to these insubstantial reckonings, starting in Part I with a critique of Dani Garavelli’s ‘Glasgow’s Reinvention has Stalled: Can we Rekindle it?’ published in October 2024 in The Glasgow Bell, and Rory Olcayto’s ‘Welcome to the Shipwreck’, first delivered as a talk to the Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland (RIAS), November 2023, then published in Architects’ Journal a month later before being republished in The Drouth, January 2024.[1] The former, I argue, is symptomatic of historical nostalgia and structural disavowal, and the latter lacks substantial ‘mooring’ in Glasgow’s decades-long political-economic restructuring. Neither bear witness to the role of political praxis in shaping urban politics and neither address the fundamental role of capitalist failure in Glasgow’s urban reshaping. Drawing out their limitations serves as a point of departure in Parts II and III for a retrospective materialist analysis of urban regeneration policy before and since the demise of Variant magazine in 2012.

I. Commentary without theory =

Garavelli’s article for The Glasgow Bell is ostensibly about the decline of Glasgow as a city of reinvention. But this assumes that Glasgow’s ‘urban renaissance’ and rebranding in the 1980s and 1990s was something other than a zero-sum game of competitive neoliberal extraction, premised on flogging off municipal assets on a grand scale, leaving the city dependent on (reluctant) inward investment and bereft of autonomy to determine ‘its’ own future. But then ‘Glasgow’ is not a ‘thing’ for which we might determine an identifiable persona (despite the efforts of multiple rebranding programmes), but a set of socio-economic relations dominated for half-a-century by the central tenets of neoliberalism and market-oriented reform: privatisation, deregulation, fiscal retrenchment, financialisation, crisis manipulation, upwards redistribution, asset stripping. This has been compounded by nearly two decades of austerity policies with the express purpose of disciplining labour and the fiscal state while state subsidy masks profound market failure in conditions of remarkable impunity––evidenced most strikingly after the 2007–08 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

To talk of what ‘Glasgow’ can do (in urban planning, in architecture) in the contemporary context is to disavow the degree to which the local authority has been emptied of autonomy by market prerogatives, fiscal discipline and austerity, and, to use an apt phrase by the architectural historian, Manfredo Tafuri, is to practice ‘form without utopia’, which for him marked the radical disjuncture between capital’s need for urban growth and purportedly progressive architectural practice.[2] But if Tafuri’s critique––influenced by Mario Tronti and the revolutionary milieu of Italian operaismo (‘workerism’)––described a time when economic growth and modernist architecture were cementing the relatively progressive but ultimately system-reinforcing Fordist-Keynesian state (integrating the trinity of capital, state and labour), the current form of urban utopia envisaged is evacuated of both economic growth (in tendential decline since the early-1970s) and architectural practice of any progressive content. Disavowing this context––whose background is the secular decline of industry and the tendential urbanisation of capital, which the Marxist intellectual Henri Lefebvre foresaw in the late-1960s––promises neither form nor utopia, but only fragments of deeply compromised development in a sea of commodified and socially redundant architectural banality. It is not that good architecture cannot still occasionally surface but that architecture, as Frederic Jameson the Marxist cultural theorist once put it, is the most imbricated of all the arts within capitalist development, and such development is now almost if not entirely shorn of any progressive, never mind socialist ethos.

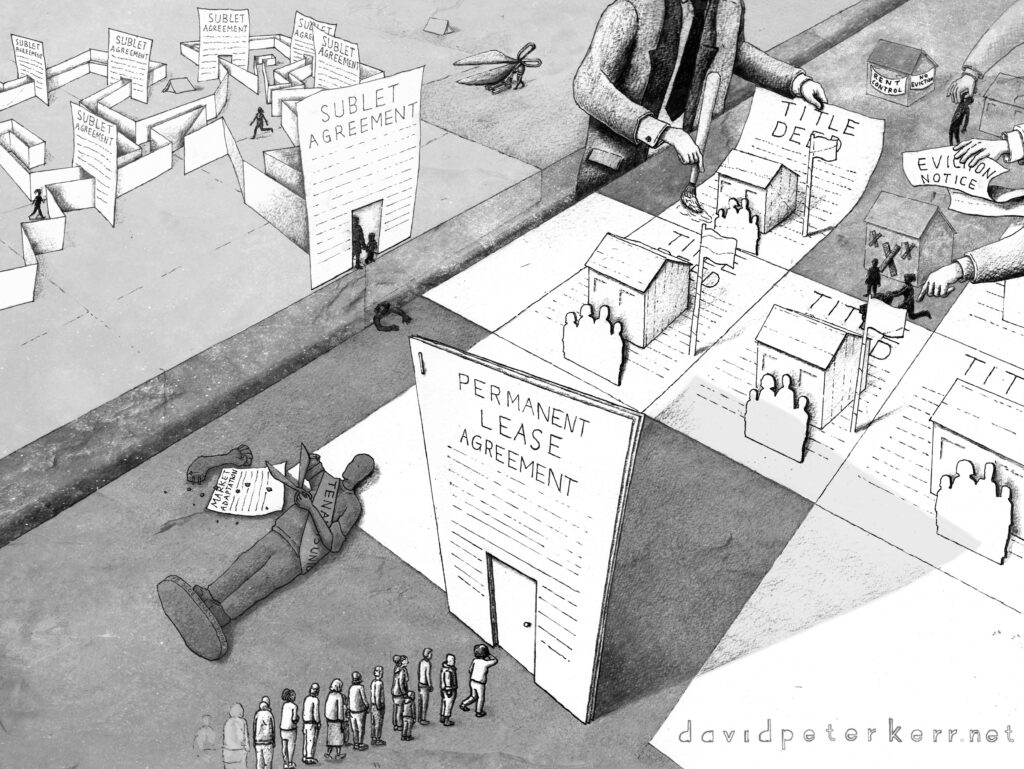

The exhaustion of generic mobile fast-policy transfer ‘fixes’ (the creative city, the sustainable city, new urbanism, temporary urbanism, the fifteen-minute city)––potentially progressive ideas of ‘soft austerity urbanism’ caught in the contradictions of underlying economic conditions––leaves us in the end with the stale reality of powerful volume housebuilders and ‘purpose built residential accommodation’ (PBRA) as the only-game-in-town.[3] The latter includes most prominently large-scale developments of build-to-rent and student housing, specifically engineered products facilitating the extraction of rent for pension funds, Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and other large global investment vehicles. Now, it is not so much what Glasgow does, but what Glasgow City Council must submit to, in a context of diminished fiscal resources, autonomy and political will. The rapidly rising heights of the relatively limited new commercial and residential buildings in Glasgow, in often inappropriate urban settings, is not an index of urban vigour but of local authority capitulation and planning submission. Likewise, the proliferation of student and build-to-rent housing along the beleaguered River Clyde signifies the abject failure of the local authority to develop the river in any meaningful way since its industrial demise. It is true that these issues are not unique to Glasgow, but it is also true that the City Council in its various political iterations has done little to fight this course of direction and in fact has pioneered new forms of neoliberal extraction in old industrial cities (of which more shortly)

What does Garavelli’s account present? Many of the complaints resonate: the city’s Victorian and Georgian architectural legacy in decay, often at the hands of absentee landlords; a public transport system taking “a perverse pride in its inadequacy”; the abandonment of the long-promised Glasgow Airport Rail Link; a series of commercial and cultural buildings demolished, left to decay or shut down; a profusion of buildings on the at-risk register (currently 143, the register is now paused); the decline of the handsome Georgian Carlton terrace on the Clyde; anger at an expressway being carved through the deeply impoverished area of Springburn for the benefit of wealthy Bishopbriggs. But then there’s the woeful bourgeois commentary: there is “shame” at the weekend drunken mating brigade, and solitary vox-pop interviews with individuals from Lenzie and Bearsden––two of the wealthiest areas in Greater Glasgow; one of whom suggests that Argyle Street is a “bit slummy”, the other frets, of all things, over the survival of Waterstones Booksellers on Sauchiehall Street. The city’s assumed “rise from the ashes” and rebranding as an entrepreneurial city in the 1980s is hailed, bereft of critical examination: “We may have sneered at lord provost Michael Kelly’s ‘Glasgow’s Miles Better’ campaign, but as the grime was scrubbed from the city’s face and beacons were lit in one dark corner after another, we could not ignore its power.” The ‘we’ here, a hubristic staple of middle-class journalism, speaks for whom exactly? Nothing is said about rising rents (more than doubling in the last decade) and the evacuation of the working-class from the city centre; nothing too of how urban transformation was achieved on the back of proto-neoliberal public-private agencies such as Glasgow East Area Renewal (GEAR) and Glasgow Action and held together by an expanding reserve army of service sector low-wage precarious labour—the damned underneath of ‘creative city’ hyperbole.

Garavelli takes a walking tour with two individuals who, to their credit, have attempted to preserve Glasgow’s built heritage in challenging circumstances: Paul Sweeney MSP, and Niall Murphy, Director of Glasgow City Heritage Trust. But here she remains uncritically in thrall to the “buzzy hotchpotch of cafes, flats and hairdressers” around Ingram square in the Merchant City, a description which is likely to present feelings of cognitive dissonance for those who’ve trespassed these typically barren domesticated streets. Meanwhile, the nearby Italian Centre on John Street, once a supposed harbinger of the new ‘post-industrial’ Glasgow, now looking outdated and redundant, is described as “the zenith of flashy Merchant City ambition”. The historical preservation of buildings in this area is to be noted in a city known for its flagrant destruction of the built environment, but these are myopic and untimely reflections for a much-hyped area of the city that has long flattered to deceive and where the overwhelming structure of feeling is not of emergence but calcification.

The so-called ‘Selfridges effect’ is briefly discussed at the adjacent Candleriggs Square, where they failed to deliver on a promised new department store, leaving the large site vacant for decades. But the ungainly and passé behemoth of the co-living/hotel/student housing ‘Social Hub’ (Drum Property Group and Stamford Property Investments) and 346-unit build-to-rent scheme on the site (Legal & General) are passed by without critical comment, despite being emblematic of the kind of global investor rent extractive development that blights UK rentier urbanism. Sweeney replicates developer concerns that new student and build-to-rent developments are under threat from (potential) impending rent controls (glossed as protecting tenants from “bad landlords” by Garavelli, rather than the odious institution of private landlordism itself). In doing so, Sweeney entirely ignores the need to address the devastating impact of year-on-year above-inflation rent increases for tenants in favour of unaffordable PBRA developments that only exacerbate Scotland’s self-declared housing emergency, while gouging rent from the city via global pension funds and asset managers like Legal & General. This at a time when Living Rent tenants’ union are doing their best to push through, with considerable reaction by the property lobby, more stringent and effective rent controls in the Scottish Parliament via the Housing Bill (Scotland) 2024.

Along King Street, the closure of The 13th Note café bar, restaurant and gig venue is ignored. A popular ‘alternative’ institution in the city since 1997, the café was shut down by the owner after workers struck over pay and conditions. More attention to this episode reveals real contradictions in the so-called creative city, which is ultimately—as even Richard Florida the guru of the creative city thesis acknowledges—reliant on the “support infrastructure” of a growing pool of underpaid, insecure service workers.[4] The workers’ revolt against these conditions, and relatedly at the Saramago café in the Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA), shattered a symptomatic silence on the precarious labour process underpinning the mythic ‘creative economy’. The owner’s solution was to shut the venue down, a fate temporarily replicated at the CCA, albeit for reasons that included labour unrest but went beyond it. The “hip” café bar/record shop Mono/Monorail, and vintage emporium Mr Ben, are described as “a tantalising glimpse of what could be”. I am a relatively frequent user of Mono/Monorail myself and the Monorail record store is an important institution in the city, but a cafe bar that opened in 2002 and closes at 10pm on weekend nights (gig nights aside) is not a vision of the future likely to enthrall anyone under 40. More apposite, yet ignored by Garavelli, is the failed vision of the future for this area as the ‘lower-east’ side of the Merchant City, a specious reference to the long-gentrified cultural mecca of lower-east Manhattan (to be discussed in more depth shortly).

Most indicative of the critical vacuity of the piece is a trip to Sighthill, a former high-rise scheme just north of the M8 motorway, where the construction of 820 new homes and the publicly funded drainage system is applauded. The tenure balance of properties is described as “controversial given the previous area’s demographics”, but any closer examination of this regeneration project deserves much robust language to catalogue a profound process of working-class erasure from the area. This is evident in the reduction of 2,500 council homes when first constructed between 1963–69, to 141 social rented homes presently. This represents a near-complete eradication of public housing (council housing) then social housing (housing associations), legitimised by long-term processes of urban abandonment, devalorisation, discourses of territorial stigmatisation and a perceived need to generate ‘mixed communities’ (with the ‘mix’ always resulting in more private housing and less public/social housing). The latter is a core policy agenda in the UK’s urban regeneration strategy, appropriately described by critical urban scholars as a ‘Trojan Horse’ for gentrification. I will address Sighthill in the second part of this article as part of a broader retrospective analysis of urban regeneration in Glasgow.

Rory Olcayto, an architectural writer and former editor of Architects’ Journal, provides a more substantive work of criticism in ‘Welcome to the Shipwreck’, though the article is suffused with an underlying idealism that dissolves in the face of material reality. His critique is familiar and relatable: parochial and banal architecture; the farce of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s renowned Glasgow School of Art building remaining long-gutted after successive fires in 2014 and 2018; the deplorable handling of several major buildings by Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson; widespread demolition as “a structure of feeling”, including most recently the well-planned modernist housing estate at the Wyndford in Maryhill; the displacement of Elspeth King, the one-time curator of The People’s Palace, a working-class museum that is now a shell of its former self; the destruction of a coherent and structurally sound townscape and the citywide tram system by the M8 motorway; the hiving off of wealthy suburbs of the region from the city’s council tax system, paying nothing for its free services. These are all valid complaints, but locating problems is not the same as developing the correct tools to fix them, often justifying more-of-the-same policies. This is evidenced glaringly by deregulatory ‘build-build-build’ policies to fix the ‘housing crisis’. A strategy that will only further inflate the housing economy while entrenching the power of already powerful volume housebuilders and financial asset managers at the expense of tenants, those financially excluded from homeownership and those massively indebted to obtain the homeownership ‘dream’.

Olcayto’s narrative starts with an ode to Glasgow’s eminently urban and global status as a grand Scottish city, but one whose wealth was in large part determined by its role in the sugar and tobacco plantations of the West Indies and the Eastern seaboard of North America. Glasgow became, Olcayto suggests, a “wonder city” of the industrial age, whose nineteenth century municipal governance was a model for emerging cities in America, though he does also acknowledges the dark underside of industrial development in Glasgow; a “hellish” polluted industrial landscape, slum housing and overcrowding matching anywhere else in Europe, appalling wage conditions perpetually threatened by cyclical industrial crises and massive reserve armies of desperate surplus labour. This grim reality still lingers, as Olcayto admits, yet any lessons from this history are hidden from the rest of the article. What he fails to mention is that the poles of influence would be partially reversed in the 1980s, when Glasgow took inspiration from the entrepreneurial pro-growth ‘downtown’ development of inner-city areas in ‘rust belt’ metropolises such as Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Baltimore and St Louis. This elision is important because the ramifications of Glasgow’s proto-neoliberal policy direction in this era are still evident today in Glasgow’s flagging hollowed-out city centre and highly uneven urban development across the city.

Other points in Olcayto’s narrative are worth further inspection and development. He notes that Glasgow has the most derelict and vacant sites in Scotland, with 36% of all Scotland’s derelict plots (a relatively well-known fact), but also usefully observes a lesser-known fact that Glasgow obtains just 0.5% of the total taxable value of all derelict land nationwide. In England and Wales, according to the critical geographer, Brett Christophers, 70% of the value of each-and-every home is attributed to land costs.[5] While no such figures exist for Scotland to my knowledge, this conforms to a global pattern of increasing land commodification to which Scotland will not be excluded. The way that local authorities manage and dispose of their limited land assets is therefore of vital importance in meeting mounting affordable housing need and social service provision, yet beyond a brief critique of limited land taxation, Olcayto does not examine the issue of local authority land use any further. I will address this question with a little more depth shortly in relation to wider regeneration strategies in the city.

Another point of note is Olcayto’s (re)telling of Reidvale Housing Association on Duke Street in the city’s long beleaguered East End, made relatively famous in the BBC documentary, The Secret History of our Streets: Duke Street. Olcayto follows the standard progressive narrative of smaller housing associations beginning in the early-1970s, deeming them pioneers of “co-design, retrofit and strategic infill”. This is framed positively as “a Glasgow idea” and there is no doubt these smaller Housing Associations helped transform how the dilapidated tenement form was viewed and lived in. But this narrative disavows or is not cognisant of how this ‘success story’ was inextricably related to the stigmatisation and de-funding of ‘monolithic’ public (‘council’) housing and opposition from community action groups at the time. It also fails to account for the tendential displacement of smaller community housing associations by larger entities over time, and the increasing privatisation, commodification and financialisation of housing associations as initially preferential funding treatment––to break public housing hegemony––gave way to diminished funding and the mute compulsion to seek more private funding from banks, and increasingly bond and capital market investors.[6] Rapidly rising rents in the social housing sector is the inevitable result and demolition as ‘a structure of feeling’, which Olcayto so decries, has been nowhere more evident than in the creative destruction of former public housing by housing associations since the stock transfer of the entire public housing stock in 2003.[7] It is not so much astonishing as typical that architectural critics and journalists discussing the state of the city have so little interest in where and how working-class people actually live beyond a few modernist ‘architectural gems’. In Part II, I discuss the regressive transformation of Glasgow’s housing provision in more detail.

Given the lack of material analysis about the economic factors underpinning Glasgow’s urban environment it is surprising that Olcayto feels he has any solutions to fix this ‘shipwrecked’ city. Even if he does well illustrate some of the symptoms of the carnage deindustrialisation and bad planning has left in its wake, it requires a certain hubris on this basis to presume he has the solutions himself at hand. But presume he does, with a sixteen-point list of magic bullet solutions for Glasgow’s urban renaissance. I will not reiterate all these suggestions here, they are available online for those who want to investigate, and they are not all bad––though many absences are glaring and the author’s own architectural predilections take centre stage. For instance, why a “presumption against demolition” in the city centre and not the suburbs where most demolition has taken place? Because the demolition of public/social housing means less to the author than ‘townscapes of note’? Why appoint “a heavyweight mayor with far-reaching power”? Because the author has no faith in collective solutions so must rely on great individuals?

What is striking is the individualised provenance of the points and the complete absence of any bargaining capacity via collective action and social force. There is no lack of good ideas in the world––multiple books, reports and practices––but it is a banality to say that these ideas are thwarted by the mute compulsions of economic growth models and the extra-economic policies that facilitate capital accumulation. How in this context, are ‘good ideas’ in themselves supposed to be implemented? (What can we do? the author asks before proceeding to say what he thinks we should do). Why does the author ignore this context––howling at the tragedy of the city’s admittedly ‘middling modernism’ period, while largely ignoring the neoliberal tragedy that followed? And why is this article so celebrated when it is ultimately just hot air? Where is the substantive critique and where are the collective voices in this account?

II. The Urbanisation of Capital

For Olcayto, Glasgow’s post-war modernism was “too extreme” and is given little further examination. There is no doubt that crashing the M8 motorway through the city centre, decimating much of the city’s tenement fabric, and mass building high-rise and low-rise public housing of generally poor quality had detrimental effects on the city’s population. But what this position misses in hegemonic terms is that since the 1930s Glasgow was no longer a city of industry but a ‘city of social reproduction’, a status only broken temporarily by industrial munitions production for the WWII and what can now be seen in hindsight as a relatively brief period of post-war Keynesianism. Glasgow’s famous post-war planning documents, the ‘Bruce Plan’ (1945), authored by Robert Bruce on behalf of the Corporation of Glasgow, and Patrick’s Abercrombie’s ‘Clyde Valley Regional Plan 1946’ (1949) for the Scottish Office, are worth reading closely. Each is remarkable for scarcely mentioning industry, which would be exiled to the New Town developments––along with the working-age population––which had limited long-term success in terms of the reproduction of capital and labour but made a major contribution to the ‘Glasgow Effect’ of excess mortality.[8] Recession, then the Great Depression, were the order of the day in the 1920s and the most significant workers’ movement of the 1930s was likely the ‘Hunger Marches’ of the National Unemployed Workers Movement.

By the late-1960s, Glasgow’s tendential industrial decline was well underway, and by the early-1970s it was widely acknowledged as the most deprived city in the UK. What Olcayto skirts over in these developments is that Glasgow’s admittedly ‘middling modernism’ was not so much a choice but a necessity to maintain a level of redistributive social reproduction in the face of massive capital flight by the industrial barons. It was an attempt to mitigate and transform the disastrous slum conditions (again, in worse condition than anywhere else in the UK) and literally toxic landscapes left over from the free play of unregulated capitalism in the ‘golden era’ of industrial development in the city.[9] Whatever its merits or demerits––mass affordable public housing on one side and appalling planning on the other––Glasgow’s post-war reconstruction must be understood as planning in a state of emergency and financial constraint. The current rounds of regeneration and urban financialisation cannot be grasped without reference to the contradictions of this period.

In Purging the Poorest: Public Housing and the Design Politics of Twice-Cleared Communities (2013), the US urban scholar, Lawrence J. Vale, finds an expression pertinent to many of Glasgow’s near inner-city communities. ‘Twice-cleared communities’ perfectly describes the succession from the devaluation and demolition of pre-war tenement communities in the post-war era to the post-2000s devaluation and demolition of the public housing schemes––often high-rise––which replaced them on the very same plots of land. In areas such as the Gorbals, Anderston, Sighthill, Govan, Dalmarnock, Pollokshaws and many other districts, demolition as ‘a structure of feeling’ has a profound historical-geographical-material resonance that is barely mentioned in the accounts of Garavelli and Olcayto. Glasgow’s current urban situation is in strong part a result of two powerful tendencies––far from confined to Glasgow alone––since the early-1970s: de-industrialisation and the urbanisation of capital (including financialisation, rentierism, assetisation and land speculation), with each reinforcing the other through cycles of endemic economic and urban crisis––processes of devaluation and (attempted) revaluation all too apparent to anyone with a keen eye on Glasgow’s urban history.

It was Henri Lefebvre, with his theories of ‘the production of space’ and ‘the urbanisation of capital’ in the early-1970s, who so perceptively theorised these tendential developments, with his conceptual innovations later being developed in more empirical form by David Harvey and a host of other critical/Marxist geographers. And yet so much current urban analysis ignores the development of capitalist urbanisation and its implications––patently obvious in commodified, financialised, rentier urban landscapes––for partial analysis and fragmented thinking that fails to address the determinate conditions of urban formations. Lefebvre was a complex thinker of ‘totality’ (that taboo term), whose thinking of abstraction was dynamic, open-ended, undetermined. He was dismissive of what he called the ‘fragmentary sciences’, which reconstruct a multiplicity of separated, fragmented spaces, and sought a revived project of ‘unity and totality’ which attempted to construct, in praxis, relations between fields and fragments hitherto apprehended separately. For him abstraction, as in its weak form, was not the exclusive privilege of thought, but ‘real abstraction’, after Alfred Sohn-Rothel, which emerges in material conditions through the abstract equivalence of commodity exchange. The title of Samuel Stein’s Capital City (2019) gives a blunt sense of what this means for the neoliberal city in practice.[10]

Lefebvre’s unitary theory was based on what Hegel termed the ‘concrete universal’, meaning that the concepts of production and the act of producing, widely understood, have a “certain abstract universality”.[11] Lefebvre’s great contribution was to apply this understanding to space through the concept of abstract space. Abstract space, he argued, “corresponds […] to abstract labour––Marx’s designation for labour in general”.[12] This conception of spatial production is clarified in the shift he advocated from an analysis of the production of things in space to the production of space itself. His notion of ‘the urbanisation of capital’ arises from this seminal concept. In just a few short passages of The Urban Revolution, first published in 1970, Lefebvre’ analysis still surpasses much of what has since passed in urban theory. His most prescient assertion––against both bourgeois science and a Marxism whose focus remained narrowly on the ‘productive worker’––was the tendential supplanting of industrialisation by urbanisation, which was becoming increasingly central to capital accumulation strategies, the economic exchange of space/habitat, and the reproduction of the relations of production. This speculative thesis was overstated at the time but presciently conveys tendential developments since––not only in old industrial cities such as Glasgow, but cities worldwide.

At the core of the urbanisation of capital, Lefebvre argued, was a general ‘switch’ of capital from the ‘primary’ sector of industry and manufacturing to the ‘secondary’ circuit of land, real estate, housing and the built environment, with real estate in the secondary circuit serving as a ‘buffer’ for the dumping of surplus capital in times of industrial malaise and economic depression: “As the principal circuit begins to slow down”, he observed: “capital shifts to the second sector, real estate. It can even happen that real-estate speculation becomes the principal source for the formation of capital, that is the realisation of surplus value. As the percentage of overall surplus value formed and realised by industry begins to decline, the percentage created and realised by real-estate speculation and construction increases. The second circuit supplants the first becomes essential.”[13]

The ‘capital switching’ idea has since been developed by numerous urban theorists, with David Harvey’s notion of capital ‘surplus dumping’ in the built environment being closely associated with the thesis. But it was Lefebvre who first grasped its political ramifications, developing a whole series of terms as an immanent dialectical response to this tendential process: differential space, the politics of space, the right to the city, and the critique of everyday life (the latter foreshadowed the development off his urban theory but would be important for the Situationist International and their unitary critique of urbanism). Harvey would later capture the meaning of these propositions concisely: “If the capitalist form of urbanisation is so completely embedded in and foundational for the reproduction of capitalism, then it also follows that alternative forms of urbanisation must necessarily become central to any pursuit of a capitalist alternative”.[14]

Housing is now central to most global political economies: it played a decisive role in the 2007–08 global financial crisis; real estate now accounts for 60% of global assets, with approximately 75% of that figure tied up in housing; asset ownership (with housing as the dominant asset) is increasingly important in determining class position in a decades-long context of asset inflation and wage stagnation; rising land prices at a global level explain about 80% of the global house price boom that has taken place since WWII. Glasgow is not immune to these fundamental processes of real estate development so why ignore them? What do we find when we examine Glasgow’s urban environment through the prism of the urbanisation of capital and not the ‘fragmentary sciences’ of architecture, bourgeois journalism, planning, technocracy, city boosterism, or any other partial, positivist view? In what follows, I begin a provisional tracing of the urbanisation of capital in Glasgow––and its contradictions, path dependencies and blockages––through recent urban regeneration projects in the city.

III. Regeneration Awry

Garavelli’s tour through the Merchant City is of interest to me since I wrote two extended articles about the district for Volume II of Variant before it was defunded by Creative Scotland in 2012. What is striking is how dated her comments are in a context of regeneration stasis or outright failure in the area and how a history of working-class erasure and state-subsidised rental extraction is deemed unworthy of mention. The Merchant City moniker, lest we forget, was part of a branding strategy designed to recreate ‘Glasgow’s entrepreneurial spirit’; a craven attempt to link notions of neoliberal entrepreneurialism with those of the past, sanitising both Glasgow’s deep involvement in the colonial economy and contemporary forms of economic and cultural looting.[15] But entrepreneurialism as a nominally private risk-taking venture was always a misnomer in relation to the Merchant City since its transformation from an area of warehousing, clothing manufacture, and the city’s largest fruit and vegetable market (production, distribution) to the current gentrified iteration (leisure, consumption) was dependent on heavy state intervention: state-aided recovery from planning blight after failed urban renewal policies, the designation of ‘Special Project Area’ status with ‘flexible’ planning in the early-1980s, and, most importantly, a generous package of public subsidies to pump-prime development. Any development risk, as Jones and Patrick observe, was underwritten by public subsidy, “which would bridge the gap between a desirable objective and a profitable opportunity”.[16] When public money is spent, we should ask who and what for? The new developments in the Merchant City primarily housed professional and managerial types (or ‘yuppies’ in the language of old), and the beneficiaries of public largesse––conversion grants, ’positive’ planning controls, release of land and buildings to developers, urban realm works, heritage initiatives––have been developers, landlords and real estate agents. As Jones and Patrick conclude in a detailed analysis from 1992, rising land values in the area (and they rose sharply) were always dependent on public money and would remain so. Indeed, the present stasis in the Merchant City can be seen as an index of an entrepreneurial void and local fiscal constraint, with the long-term stagnation of Argyll Street evidencing the limits of Merchant City regeneration.

Garavelli’s rendering of the Mono café bar and restaurant on King Street as a vision of ‘what could be’ provides an opportunity to assess the City Council’s actual vision for the area and what has since transpired. In 2009, I critiqued the City Council’s weak replication of now thoroughly debunked and irredeemably tired creative city policies. The so-called Artist-Led Property Strategy inverted its own terms by virtually dragging artists into the area to facilitate planned gentrification, and the chronically passé nomenclature of ‘Lower East’ Merchant City was conjured (and never uttered by anyone outside a planning or marketing office) to spuriously connect local development plans with the creative zenith, and later gentrification, of Lower East Manhattan. At the time, I observed that any growth of the so-called creative class “would be far outstripped by the concomitant growth of an increasingly insecure service class”.[17] With the closure of the 13th Note café bar and gig venue––covered in more detail by Communal Leisure in this issue––the fictive and precarious nature of the creative city model was exposed with both ‘classes’ wiped from an area where footfall diminishes with each passing year, despite the stalwart efforts of Mono.[18]

At the same time, the historic Paddy’s Market, located in Shipbank Lane since 1935, was in the process of being eradicated as a “crime-ridden midden” to create “a mini-Camden market” in its wake.[19] Councillor George Ryan, then City Council regeneration convener, had this to say: “It is the death knell for the anti-social element. We want to move all that out. We want to up the bar of what we expect from a market right in the heart of the city. We want to bring in a better class of retail there”.[20] Paddy’s Market, after continual police raids, demonisation and protests by market traders was shut down in 2009 but the planned tourist destination, arts and crafts market and cultural venues at the railway arches, like so many regeneration plans in Glasgow, were never realised. Meanwhile, King Street car park, which has long prohibited any coherent plan for the area, has been through numerous failed planning applications. The latest by Vengada estates is for a mixed-use development with the usual cursory branding: ‘The Merchant Quarter’.[21] The proposal combines offices, a hotel and retail/leisure with the inevitable recourse to build-to-rent, student housing and co-living residential units––the only game in this town, and others across the UK, when all else fails.

If Merchant City gentrification is premised on the ‘marks of distinction’ resulting from Glasgow’s irrevocably tarnished colonial and Victorian architectural heritage, the three main large-scale urban regeneration projects in Glasgow since the early-2000s map onto primary areas of industry and its decline, indexed by the largest proportions of vacant and derelict land in the city: the central River Clyde Waterfront, the Clyde Gateway project in the East End, and Sighthill in North Glasgow. Following the Garden Festival of 1988, the Clyde Waterfront regeneration project has made slow progress with limited and privatised results. The riverside remains an alienating, fragmented and disjointed landscape along an “almost dead river” fronted by isolated large buildings and car parks, and a lack of basic amenities (toilets, shelters) or continuous walkway that might attract people to the river. The buildings loom in isolation like a fractured Stonehenge of defeated capitalism. There are surprisingly few critical studies of regeneration on the River Clyde, reflecting a broader disinterest in regeneration failure in the academic and policy literature, but Georgiana Varna provides some useful insights, providing three main reasons for regeneration failure: lack of local authority vision, coordination and ‘placemaking’ ability; fiscal crisis, empty public purse; divided land ownership and conflict between the three main development stakeholders––Glasgow City Council, Scottish Enterprise and Clydeport (part of Peel Ports), the former Port Authority. These factors, which refract the determinate conditionalities of the neoliberal present, have prevented long-term coherent master planning, producing a highly uneven and unattractive patchwork of private ventures and vacant sites, broken only by the publicly funded Riverside Museum on the northside of the river, which lies in splendid isolation.

In a context of long-term market and state planning failure, the main spatial fix is ‘Purpose Built Residential Accommodation’ (PBRA), with build-to-rent and student housing featuring particularly strongly (the other PBRA option, ‘co-living’ is not yet advanced in Scotland). Beyond an excellent PhD by Eoin Palmer on build-to-rent, PBRA has not been studied with much depth in Scotland.[22] Yet it is tailor-made for the needs of international real estate investors and developers rather than local districts, where it is imposed by the property lobby, policy wonks and local state managers devoid of ideas. Why? Capital has always sought more liquidity in the built environment, which unlike other commodities tends to be ‘fixed’ in time and space with long turnover times. PBRA, contained in single developments (often with up to 400 rooms), with single landlords and management, provides a ‘spatial fix’ for this problem, facilitating the smooth flow of capital through urban space in the form of predictable and standardised features––as opposed to the ‘anarchy of the market’ in variegated landlordism––facilitating easier exchangeability and marketability. The structural shift towards PBRA portfolios lends itself perfectly to international real estate investors (pension and equity funds, REITS and the like), who restlessly seek new markets with steady returns (guaranteed by built-in rent increases over time) to facilitate the dumping of swollen capital surpluses in the built environment. The landscape of the River Clyde is theirs not ours and the local state’s facilitation (or capitulation) to this form of development is an index of quarter of a century of regeneration failure on the Clyde and a property market favouring capital liquidity over social rented housing.[23]

Another area riven by market failure, but propped up by copious amounts of state subsidy, is the Clyde Gateway regeneration project. Sitting on roughly the same area as the Glasgow Eastern Area Renewal (GEAR) project (1976–87)––a pioneering (failed) public-private partnership initiated six years before the London and Liverpool Docklands regeneration projects––development was premised on decades of urban devaluation. At the beginning of the project in 2008, out of a total of 840 hectares of land, 350 hectares (more than 40%) was classified as ‘vacant and derelict’. These conditions of large-scale urban devalorisation provided the necessary conditions for potentially profitable revalorisation, but something more was required. Winning the bid in 2007 for the 2014 Commonwealth Games (within the Clyde Gateway area) and the highly contested approval of the M74 motorway, provided the necessary infrastructural and public funding catalysts to approach the East End as a ’new urban frontier’ of urban capital accumulation, with territorial stigmatisation––of land, buildings and people––providing another neoliberal alibi for a state-facilitated land grab.[24]

But Glasgow is not London. Attracting private investment to relatively impoverished old industrial cities is fraught with difficulties, especially in large-scale areas of contiguous urban devalorisation with marginal locations, limited consumer power, poor amenities, vacant, derelict and contaminated land and other investment inhibiting factors. The free market mythos of equilibrium between supply and demand falls apart in such conditions. In the case of Clyde Gateway, addressing market failure meant closing what I’ve called the ‘state subsidy gap’, the economic gap that must be bridged by the state to make a currently unviable urban investment scenario potentially profitable for private developers. Two of the main developments within the project are illustrative.[25]

First, for the 2014 Commonwealth Games Athletes’ Village, a series of what the Glasgow Games Monitor 2014 termed ’dodgy land deals’ took place, costing the City Council £30 million to parcel land for development and delivering extremely profitable sales for developers who had purchased land just before the bid for the 2014 Games was won.[26] The site also benefited from £7.7 million from the Scottish Government’s Vacant and Derelict Land Fund, absorbing financial risk for the developers of the Athletes’ Village, City Legacy Consortium, who were gifted the entire site at ‘nil cost’ to avoid any problems the consortium might face raising private finance. A full decade after the Games, the second phase of the development has yet to appear despite these inducements. Second, the Shawfield National Business District on the former site of J & J White’s Chemical Works is requiring around £100 million to remediate chromium contamination and address poor quality infrastructure and fragmented land ownership patterns. To date, only one office block has been developed, the Red Tree Magenta, whose £9 million construction costs were met by Clyde Gateway, the Scottish Government and South Lanarkshire Council. In what amounts to a begging later for more state subsidy in the face of market failure, Clyde Gateway have stated: “There can be no argument that without intervention by the public sector, of which Clyde Gateway is currently the main vehicle, market failure will remain”.[27]

Urban regeneration in Sighthill condenses a three-fold pattern of public housing residualisation and gentrification that has been writ-large across Glasgow since the 1980s: drastic housing reduction, sustained devaluation and disinvestment, and ‘poverty deconcentration’ through mixed communities or mixed tenure policies. This pattern is climaxing in the Transforming Communities Glasgow (TCG) programme, a Special Purpose Vehicle partnership led initially by the Glasgow Housing Association (GHA), Glasgow City Council (GCC) and the Scottish Government.[28] Approved by Development and Regeneration Services in 2007 and ratified by the Scottish Government in 2009, it covers eight Transformational Regeneration Areas (TRAs): East Govan/Ibrox, Gallowgate, Laurieston/Gorbals, Maryhill, North Toryglen, Pollokshaws, Red Road/Barmulloch and Sighthill. These areas were almost exclusively comprised of high-rise social housing and all have been subject—with varying degrees of severity—to sustained disinvestment, residualisation and territorial stigmatisation.

The Sighthill TRA has been self-described as ‘the largest regeneration project of its kind outside London’. Following slum clearance in the post-war era, between 1963–69 ten 20-storey slab blocks were constructed along with several lower-level buildings, providing around 2,500 public housing homes. After sustained disinvestment and territorial stigmatisation related to asylum issues and new regeneration proposals, and the city-wide stock transfer of 83,00 public housing homes to GHA in 2003, the blocks were demolished piecemeal between 2008–16 despite a long war of attrition with local tenants.[29] But the promise of replacement social rented housing has been much reduced since 2007, when 1,200 new private homes and 800 homes for social rent were proposed. The social rent component is now 141 social rented homes provided by GHA, with 826 private homes (628 for sale, 198 for mid-market rent) provided by Keepmoat Homes.[30] Private sales prices start around £269,000—significantly above the average £180,000 purchase cost for a home in Scotland. It is pertinent to note at this point that each public home stock-transferred and then demolished on this site, was sold off for £310 in 2003.[31]

The TCG programme was seen by GCC as an opportunity to transform areas of predominantly social rented stock into new, mixed tenure housing, making explicit the policy assumption that ‘mixed tenure’ policy (which only ever mixes one way) should target predominantly social housing areas.[32] As with many tenure-mix programmes, the shift from social to private tenure is profound. Figures have been subject to frequent revision, but initial plans for the Early Action Programme in 2007 envisaged the demolition of 11,000 primarily high-rise GHA social rented homes—described bloodlessly as “ineffective units” in Glasgow’s 2021 Strategic Housing Investment Plan—to be replaced by 6,000 homes for private sector new build and 3,000 social rented new build.[33] This represented a proposed loss of 8,000 social rented homes in the city. But current figures go much further. Across the TRA programme, an estimated 6,500 homes for affordable sale or mid-market rent are planned with only 600 homes for social rent.[34] Fully realised this represents a reduction of 10,400 social rented homes in Glasgow. This erasure of local tenants and residents and calculated domicide of social housing has been sanctioned and sanctified by GHA (later Wheatley Homes), GCC and the Scottish Government, with Wheatley plying typical pseudo-scientific discourses of obsolescence to legitimise demolition, displacement and gentrification, describing homes planned for demolition as “unfit for modern life”.[35] This is the process––not detailed but skimmed by Garavelli––as “controversial given the previous area’s demographics”.

Conclusion

This is a necessarily abbreviated account limited by its focus on urbanisation and relative neglect of the labour process. But in at least attempting to grasp the general tendency of capitalist urban development in Glasgow––replicated with different modalities in cities worldwide––it suggests the scope and centrality of the urban mode of accumulation in the city. A customary response to broader critical analyses of pervasive capitalist subsumption is to consider such interpretation as disempowering since the ‘enemy’ is presented as too large to defeat and too big to fail. Or another response, forged from the arse-end of postmodernism and the fetid heart of liberalism, is to say that such accounts are economically reductive. But these responses themselves are inversely reductive since they routinely obfuscate and disavow clear empirical developments in the formation of cities worldwide, and the tight imbrication of culture, leisure and capital. What results is a hotch-potch of partial, fragmented views and a churn of cursory blog pieces that conserve the status quo with minor progressive deviations depending on the author’s own particularity or specialism. But addressing the urbanisation of capital frontally makes it abundantly clear that nothing less than a profound transformation of political economy––in lieu of its supersession––is required to mitigate the disastrous economic, social and ecological consequences of contemporary urban development.

Of course, such a transformation does not appear imminent, but if starting from what is required (on a spectrum of necessary decommodification) rather than what miniscule reforms (if any) are considered feasible in the realpolitik of the day, then a different political horizon emerges. Given a housing emergency––self-declared by the Scottish Government and numerous local authorities––it is notable that neither Garavelli nor Olcayto refer to any initiatives by housing activists most engaged in these issues, most notably, Living Rent, Scotland’s tenants’ union. Rent control was won––not given by enlightened leaders––through militant collective tenant organisation in the 1915 Clydeside Rent Strikes. It was finally repealed (and seemingly forgotten) after numerous battles between tenants, the state, and real estate lobbies in the Housing Act 1988.[36] Living Rent were instrumental in changing the discourse and re-establishing rent controls (albeit in unsatisfactory form) in the Private Housing (Tenancies) (Scotland) Act 2016 and are the major protagonists in strengthening existing controls through the Housing (Scotland) Bill currently proceeding through parliament. Tighter rent controls are a necessary measure to mitigate the power of landlords and rack-renting but insufficient in themselves to decommodify the political economy of housing. That will require concerted demands and action for public housing, a position which Living Rent and other tenant unions and organisations in the UK are increasingly moving towards.

Another notable case is the Wyndford scheme in Maryhill, where the architect, Malcom Fraser, and architectural conservationist, Miles Glendinning, worked closely with the Wyndford Residents Union (WRU) to prevent the demolition of high-rise housing blocks in the area. Three of the blocks are down with one to go––with all the social housing reduction and environmental waste that entails––but tenant-led campaigning has at least shifted the provision of planned new housing from commodified (and unaffordable for most locals) mid-market rent to social rent. Beyond existential wailing, structural disavowal and individualised magic bullet approaches to urban decline, this case offers a suggestive collective model, where tenants, architects, conservationists, engineers––an alternative retrofitting plan was commissioned––work together to resolve concrete, generalised problems in the urban environment in ways that might be replicated at scale.[37]

If addressing the urbanisation of capital as a hegemonic tendency seems daunting, it is not hard to find fractures in the edifice of current housing policy and regeneration strategies. Beyond fait accompli narratives of inevitable gentrification, the reality in Glasgow is more often of market failure and state rescue. The regeneration projects described above, and more besides, have either faltered or developed along tortuously slow paths, often remaining incomplete even after decades of city boosterism and enormous amounts of state subsidy as a form of upwards redistribution. Capitalist growth has been on the decline for decades and this is reflected in a switching of crises from industry to the built environment, where assetisation, financialisation, and the rentier economy divert investment and money from the productive economy and exacerbate extreme forms of inequality based on contingent access to assets, especially housing. We don’t need to sing hymns to the productive economy to see that the general political confusion evident in the present is a symptom of capitalist failure and its inability to ensure economic and social reproduction. Urban crisis should be seen as a manifestation of broader economic crises––with market failure and developer profit margins routinely propped up by state subsidy at the expense of basic social reproduction in the city––and it is these contradictions that might provide a starting point for seriously intervening in the urban problematic.

Dani Garavelli, “Glasgow’s reinvention has stalled. Can we rekindle it?” The Glasgow Bell, October 5, 2024. https://www.glasgowbell.co.uk/glasgows-reinvention-has-stalled-can-we-rekindle-it/; Rory Olcayto, “Welcome to the Shipwreck,” Architects’ Journal, December 19, 2023. https://cdn.rt.emap.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/12/18161041/Glasgow_Shipwreck%E2%92%B8Rory_Olcayto.pdf ↑

Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1976). ↑

For a discussion of ‘soft austerity urbanism’, see Neil Gray, “Neither Shoreditch nor Manhattan: Post‐politics, ‘soft austerity urbanism’ and real abstraction in Glasgow North”. Area, 50, no.1 (2018), 15–23. ↑

Neil Gray, “Glasgow’s Merchant City: An Artist Led Property Strategy,” Variant, 34 (Spring), (2009), 14. ↑

Brett Christophers, The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Britain (London: Verso, 2019). ↑

Neil Gray, “Nothing Exceptional: Scottish Housing Associations and the Erasure of Scottish Social Housing,” Bella Caledonia, March 30, 2018. https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2018/03/30/nothing-exceptional-scottish-housing-associations-and-the-erasure-of-scottish-social-housing/ ↑

Vikki McCall and Gerry Mooney. “The repoliticisation of high-rise social housing in the UK and the classed politics of demolition.” Built Environment 43, no.4 (2018), 637–652. ↑

See Chik Collins and Ian Levitt, “The ‘modernisation’ of Scotland and its impact on Glasgow, 1955–1979: ‘unwanted side effects’ and vulnerabilities.” Scottish Affairs 25, no.3 (2016): 294-316. ↑

For an expanded development of this argument, see Chapter 5, Neil Gray, Neoliberal urbanism and spatial composition in recessionary Glasgow. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow (2015). https://theses.gla.ac.uk/6833/ ↑

The sub-heading of the book is Gentrification and the Real Estate State. ↑

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991), 15. ↑

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 307. ↑

Henri Lefebvre, The Urban Revolution (Minneapolis: University of Minnesotta Press, 2003), 160 ↑

David Harvey, Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution (London: Verso, 2012), 65. ↑

Neil Gray, “The Tyranny of Rent,” Variant, 37 (Spring/Summer) (2010). ↑

Colin Jones and J Patrick, “The Merchant City as an example of housing-led regeneration,” in Patsy Healy et al, Rebuilding the City: Property-Led Urban Regeneration (London; New York: E & FN Spon, 1992), 132. ↑

Neil Gray, “The Merchant City,” 17, ↑

The notion that the so-called ’creative class’ was indeed ever a class is of course ridiculous. ↑

Neil Gray, “The Merchant City,”, p.18 ↑

Neil Gray, “The Merchant City,”, p.18. ↑

https://merchant-quarter.co.uk/ ↑

Eoin Palmer, Land, rent and the value-form in the redevelopment of Fountainbridge. PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh (2024). https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/41975 ↑

See Neil Gray, “If Beith Street Could Talk: ‘Build to Rent’, Studentification and ‘Purpose Built Residential Accommodation’”, Bella Caledonia. February 9, 2021. https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2021/02/09/if-beith-street-could-talk-build-to-rent-studentification-and-purpose-built-residential-accommodation/ ↑

Neil Gray, “The Clyde Gateway: A New Urban Frontier,” Variant, 33 (Winter) (2008). https://www.variant.org.uk/pdfs/issue33/v33_gray.pdf; Neil Gray and Gerry Mooney, “Glasgow’s new urban frontier: ‘Civilising’ the population of ‘Glasgow East’.” City 15, no. 1 (2011), 4-24. ↑

For a considerably more detailed critical analysis of urban regeneration in the Clyde Gateway project, see Neil Gray, “Correcting market failure? Stalled regeneration and the state subsidy gap.” City, 26(1) (2022), 74–95. ↑

Glasgow Games Monitor 2014. “Dodgy land deals in Dalmarnock.” January 17, 2012. https://gamesmonitor2014.org/dodgy-land-deals-in-dalmarnock/ ↑

Clyde Gateway. Clean Land, Clean Water: No More Poisons Beneath our Feet: The Case for the Completion of the Shawfield Remediation Strategy. Glasgow: Clyde Gateway (2019). ↑

GHA would later be incorporated into Wheatley Homes Glasgow, Scotland’s largest social housing landlord. ↑

Neil Gray, “Neither Shoreditch nor Manhattan.” ↑

Scottish Housing News, “First residents move into new homes at Sighthill,” March 9, 2022. https://www.scottishhousingnews.com/articles/first-households-move-into-new-homes-at-sighthill ↑

Norman Ginsburg, “The privatization of council housing.” Critical Social Policy 25(1) (2005), 115–135. ↑

Glasgow City Council, City Plan 2 (Glasgow: Glasgow City Council, 2009).97. ↑

Glasgow City Council, Glasgow’s Strategic Housing Investment Plan 2022/23 to 2026/27 (Glasgow: Glasgow City Council, 2021). ↑

Information no longer available online. See Neil Gray, “Neither Shoreditch nor Manhattan.” ↑

Wheatley Homes. “Regeneration.” N.d. https://www.gha.org.uk/about-us/regeneration ↑

Joseph Melling, Rent Strikes: People’s Struggle for Housing in West Scotland, 1890-1916 (Edinburgh: Polygon Books, 1983); Neil Gray (ed) Rent and its Discontents: A Century of Housing Struggle (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018). ↑

Fraser/Livingstone Architects, “The Fight to Save Wyndford.” June 19, 2013. https://fraserlivingstone.com/news/the-fight-to-save-the-wyndford ↑