Britain is an altered state—altered out of all recognition—even in the past ten years. The question for political movements in Scotland seeking transformative change is how do we respond and adjust to these profound changes.

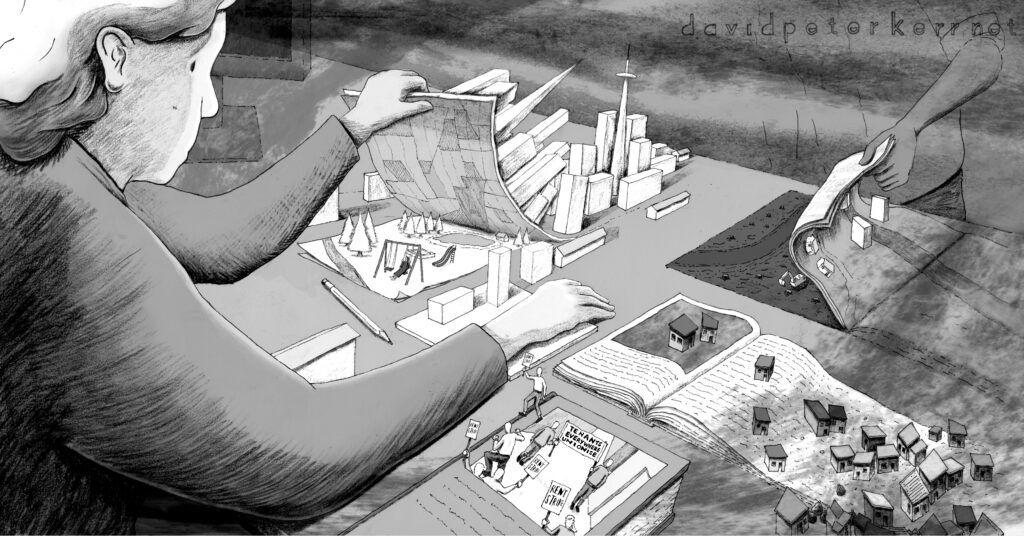

The United Kingdom’s role in the world has shifted dramatically by its withdrawal from Europe, its geopolitical position has been deeply affected by the trauma of Trump’s foreign policy and by years of turbulent and chaotic Conservative government. Socially and economically, it is diminished by years of austerity, by the stress of the virus and lockdown and by decades of neoliberal hegemony. It suffers from grotesque social inequality, a job market characterised by low-pay and precarity, an urban and rural housing crisis, and spiralling destitution with the proliferation of foodbanks now so ubiquitous that they have become part of the fabric of everyday life.

Alongside all of this we have an ongoing unresolved constitutional crisis with growing demands for a border poll in Ireland, and increased support for Scottish and Welsh independence. We have both a ‘stateless nation’ in Scotland and a ‘Union’ which has morphed from being presented as a ‘family of nations’ and a ‘partnership of equals’ to being presented as a unitary state, a nation in itself. Added to this we have seen the rise of ethno-nationalism in England, with race-riots across the country in the summer of 2024.

The palpable sense of decline is mixed with a sense of confusion of identity and purpose. The loss of any cohesive sense of British identity has long been charted in Scotland, but unsurprisingly this lack of commitment isn’t confined to our borders. A poll by The Times (February 2025)[1] found that “Half of Generation Z think that Britain is a racist country and only a tenth would risk their lives to defend it in a war”. Shocked, The Times stated: “An authoritative study into the views and beliefs of Generation Z adults—those aged 18–27—carried out with YouGov and Public First has revealed a deep erosion of faith in Britain.”[2] This collapse in ‘national identity’ isn’t just about the relations between nations within the ‘UK’ but between generations.

Britain itself has become a chimeric entity, a hallucination that flickers in and out of sight. It is revealed and projected through the faltering banality of the dysfunctional royal family, its flag is flown on official buildings but has largely been abandoned by ordinary people in all four nations other than within subcultures.

As Anthony Barnett has written[3]:

When David Cameron called for a referendum in the hope of skewering Ukip, he calculated that Farage’s obvious bigotry would have ensured a reluctant majority for staying in the EU. But many other fig ures shared a belief that, once ‘freed’ from the EU, Britain could find its way back to the greatness of Thatcher. Among the most significant of these was Paul Dacre, then editor of the Daily Mail. Fearing the loss of his last, best opportunity, in February 2016 he plastered this huge headline across his paper’s front page: “Who will speak for England?” His furious editorial demanded that acceptable politicians capable of winning (such as Michael Gove and Boris Johnson) step forward to take the lead in the referendum from the likes of Farage. Buried within the editorial was a telling aside: “Of course, by England… we mean the whole of the United Kingdom.

This subtle overlaying of England over Britain is an inevitable result of Brexit, which was an expression of both carefully nurtured racism and English nationalism, and has resulted in the undermining of the devolution settlement by the ‘internal market’ rules and the powers that were once outsourced to Europe being seized by Westminster rather than returned to Holyrood.

As Anthony Barnett concluded of the Paul Dacre editorial:

If you are English, you need to read this sentence out loud while imagining what it must be like to be Scottish, Irish or Welsh. Dacre was not calling on leaders to speak for England. He is calling for the opposite, leaders who will make a claim on all the nations of the archipelago that make up Britain. This is the “narrative” – an English insistence that our role in the world is to be “Great Britain” – that won the 2016 referendum!

At the heart of the changes that have taken place over the last decade is a profound confusion about national identity. Brexit did not, as some had hoped, result in a ‘Britannia Unleashed’ [4] or a ‘Global Britain’. It resulted in the shambles of Theresa May; ‘the hostile environment and public pedagogies of hate’ with vans touring the country urging people to ‘Go Home’.[5] It resulted in the ‘party time’ government of Boris Johnson, famously described by the head of the ‘No’ campaign Blair MacDougall as a ‘clown’ who would never become Prime Minister in August 2014.[6] It resulted in the (very) brief appointment of Liz Truss as Prime Minister.

Late Britain, Hyper Normal Island

These profound changes unfold like a rolling omni-crisis, social breakdown interplaying with the rise of fascist forces, paranoia mingling with ‘libertarianism’,[7] lockdown combining a sense of delirium with unease about mission creep and authoritarianism. The idea of these being end-days for an Old Order in Britain is both covered-up and revealed by the constant attempts to overlay decline and deterioration with spectacle and pageantry. This reached its apogee with the ceremonies surrounding the death of Queen Elizabeth in 2022 with rolling media coverage that combined the genuine grief of some with a kind of grinding tedium, an exercise in state propaganda that reached fever-pitch with Penny Mordaunt’s sword-carrying escapades. The BBC solemnly reported: “While Ms Mordaunt’s teal outfit—with a matching cape and headband with feather embroidery—also caught people’s attention, with many drawing comparisons with Henry VIII’s second wife Anne Boleyn.”[8]

The MP and Leader of the House of Commons said she was honoured to be involved in the ceremony through her role as Lord President of the Council – an ancient role.

She carried the 17th century Sword of State made for Charles II into Westminster Abbey, and exchanged it for the Jewelled Sword of Offering, which she delivered to the archbishop.

She then carried the Jewelled Sword of Offering, with hilt encrusted with diamonds, rubies and emeralds, for the rest of the service and walked with it in front of the King as he left the abbey.

Notably, she becomes the first woman to carry and present the sword—which symbolises royal power and the King accepting his duty and knightly virtues.

This gently soporific culture tends to a general quietism, a sense of all pervasive deference. The high-point for many of the whole state mourning for the late Queen was the coverage of endless queuing in line to pass by the coffin. That endless waiting, that endless patience as the ultimate virtue of Anglo-British society is held up by some as a signifier of all that makes Anglo-Britain great (again).

I’d suggest it’s a sign of a sort of crippling fealty, the manifestation of the disempowerment of being a Subject. If we look for examples of regimes and systems that are revered and respected we might look at the final years of the Soviet Union as comparable with how we are understanding Late Britain and the cultures which uphold it.

Brandon Harris has written:

The anthropologist Alexei Yurchak, in his 2005 book, Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation, argues that, during the final days of Russian communism, the Soviet system had been so successful at propagandizing itself, at restricting the consideration of possible alternatives, that no one within Russian society, be they politicians or journalists, academics or citizens, could conceive of anything but the status quo until it was far too late to avoid the collapse of the old order. The system was unsustainable; this was obvious to anyone waiting in line for bread or gasoline, to anyone fighting in Afghanistan or working in the halls of the Kremlin. But in official, public life, such thoughts went unexpressed. The end of the Soviet Union was, among Russians, both unsurprising and unforeseen. Yurchak coined the term “hypernormalization” to describe this process–an entropic acceptance and false belief in a clearly broken polity and the myths that undergird it.

The End of Britain will be both unsurprising and unforeseen. Just as The Times was ‘shocked”’ to see the views of Gen Z towards ‘Britain’ in their polling, no-one who has had a critical eye to the collapsing social order or the fractured sense of identity would be remotely surprised.

The dark irony is that it is the very cultures that have been created to maintain the status quo that mask its deterioration from its most fervent supporters. The British system has been so successful at propagandizing itself, at restricting the consideration of possible alternatives, that few within British society, be they politicians or journalists, academics or citizens, could conceive of anything but the status quo until it was far too late to avoid the collapse of the old order.

2000 AD — 2025

The Constitution of old England-Britain once stood like a mighty dam, preserving its subjects from such a fate; nowadays, leaking on all sides, it merely guides them to the appropriate slope or exit. Blairism reformed just enough to destabilise everything, and to make a reconsolidation of the once-sacred earth of British Sovereignty impossible. As if panicked by this realisation, his government has then begun to run around in circles groaning that enough is enough, and that everything must be left well alone. The trouble is that everything is now broken – at least in the sense of being questioned, uncertain, a bit ridiculous, lacking in conviction, up for grabs, floundering, demoralised, and worried about the future.[9]

If things seemed broken “a bit ridiculous… floundering, demoralised, and worried about the future” in Nairn’s 2000 account of Britain, try fast-forwarding to today. Of course the British Constitution itself would show how vulnerable it was when Prime Minister Boris Johnson ‘prorogued Parliament’—shutting it down to limit the time available for MPs to prevent a no-deal Brexit before the October 31 deadline.

Ultimately the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in R (Miller) v The Prime Minister and Cherry v Advocate General for Scotland that the advice was both justiciable and unlawful; so the Order in Council ordering prorogation was quashed, and the prorogation was deemed “null and of no [legal] effect”. When Parliament resumed on the following day, the prorogation ceremony was expunged from the Journal of the House of Commons and business continued as if the ceremony had never happened.

But if the legal ruling was held up as system correction and proof of the strength of the (unwritten) constitution, it also revealed its vulnerability to reckless authoritarianism and executive power, in this case being wielded by the ‘clown’ who would never become Prime Minister.

If the constitutional and economic chaos of the Conservative era (2010–24) was supposed to be replaced by something that would provide calm and a salve to Nairn’s instability and brokenness, this is not what has happened.

The Labour Party under Keir Starmer ascended to government in 2024—after a long long period of chaotic Conservative rule—but it was a ‘landslide’ victory derived from a small percentage of the vote, and one that has produced almost immediate bitter disappointment and recriminations even from those who supported them. Having campaigned on a message of ‘Change’, Labour immediately announced sweeping cuts and a programme of austerity mirroring precisely George Osborne’s fiscal plans. Their latest announcements, to slash overseas aid and welfare for people on disability benefits in order to fund a massive programme of rearmament has been backed by Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar.

The consequences of this are barely recognised. But the subterranean currents that have been flowing for decades are about to burst their banks, just as Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood have turned to Thames Water’s Rivers of Shit. What’s been revealed by these developments is that in the UK we effectively live under one totalising economic system delivered by a variant of parties with different characters and slogans who take turns in office but are unified around most of the diagnosis of the problems we face—and the solutions on offer. On the constitution and economic and social policy the Starmer-Reeves government is indistinguishable from the Cameron-Osborne one. Little is being said or recognised about the consequences of this for the Union, and the case for it which has evolved, morphed and deteriorated since the independence referendum.

This is not what was supposed to happen, nor what was predicted. For years the dutiful scribes and editors of the Fourth Estate predicted an incoming Labour government as both a return to social progressiveness and constitutional reform. This would put paid to the unnecessary divisiveness of nasty nationalism and pave the way for increased devolution or federalism and a strengthened and enhanced United Kingdom. The fabled ‘reform of the House of Lords’ was, we were told, just around the corner. Gordon Brown’s ‘blueprint’ was constantly cited as the source for such hopes.

Brown’s grandly titled: ‘A New Britain: Renewing our Democracy and Rebuilding our Economy, Report of the Commission on the UK’s Future’[10] landed with a big clunky-fisted thump in 2022 and has been ignored ever since.

It was a strange document.

While the report scatters scraps of odd powers to the ‘nations and regions’ it has a strange absence at its very heart. The nation for which this document has really been prepared doesn’t appear in its pages. As Kirsty Hughes writes: “Somewhere missing in this is England as a whole. Brown’s report talks of a ‘Union of Nations’ but the strangely absent England remains the heart of power & dominance where Westminster still effectively acts as the UK and England’s government. It’s the shadowy elephant in the room…”

And yet, much of the report is aimed at English voters and based on English political innovations. In this respect it pretends that devolution hasn’t really happened, and certainly that the Better Together campaign never did.

Brown is now a marginal figure, lauded in Scotland and marked as ‘elder statesman’ but really concentrating mostly on the marginal chore of improving the state of Britain’s burgeoning food banks, as grotesque inequality blooms.

But this fantasy of the British nation, which has replaced the concept of the Union, is difficult to sustain. Post-indy Britain and post-Brexit England are difficult to imagine as coherent entities.

There are very good reasons for this. The rise of an explicit English nationalism surges against this notion of Britain and Britishness. UKIP, Reform, Britain First, and the (now defunct) English Defence League all play with tropes of Englishness, Spitfire Nationalism, and a recurrent theme of repelling foreigners. Not all forms of English nationalism are as rebarbative, but the dominant forces have been expressions of the far-right. Added to this the changing nature of Irish politics makes this notion of a united British nation impossible. The economist David McWilliams wrote back in 2017: “If Britain leaves the EU, it could start a domino effect—at the end of which is a united Ireland” adding, “Relative to the South, the Northern economy has fallen backwards since the guns were silenced. If there was an economic peace dividend, it went South.”

In a considered piece analysing shifting allegiances, birth rates and demographics, McWilliams added:

A cursory glance at the performance of the Northern Irish economy since 1922 would suggest that the Union has been an economic disaster for the people of Northern Ireland. They have been impoverished by the Union and this shows no sign of letting up. The only solace the Northerners might hold onto is the fact that all British regions have lost out income-wise to Southern England; however, ‘we’re all getting poor together’ is hardly a persuasive chorus for an ode to the Union.

Though Irish unity or even a border poll is by no means certain, Northern Ireland and Ireland have baked into the Good Friday Agreement an ‘opt out clause’, setting out explicitly the terms for which a poll on reunification would be granted. Scotland has no such option.

All of this, never mind growing disillusionment and anger in Wales makes the notion of ‘Britain’ as a unifying, coherent or credible concept unlikely.

This is now an economic basket case sustained on pure ego, unprotected by constitution, and consumed by political opportunism. The delusion is fading. We are now in a moment where constitutional crisis is colliding with, not economic uncertainty but dire economic certainty

This is where we are ten years on from 2014.

Lost Futures

At the time of the independence referendum of 2014, we were (or some of us were) aspiring to create the conditions for real change. “Britain is for the rich, Scotland can be ours” was the slogan, and the packed live public meetings, protests, and cultural outpouring felt to be part of an insurgency at times. This energy was infectious and you could see it gathering momentum. There were multiple points of leadership, the map of Yes campaign groups and projects across the country flourished and the issue of self-determination was being used as a lens to look at power, feminism, peace and disarmament, land reform, the monarchy in an endlessly iterative process. People were awakened politically in a way I’ve never seen. But there was something more going on here because people were giving their whole selves to the cause in an outpouring of enthusiasm. People were beginning to dream of a better future and to believe they could have a real-world impact.

For hundreds of thousands of people the 2014 independence referendum was the high point of their political lives. It was a moment in time when real change felt possible, possibly for the very first time, when live public events were packed and people who had previously been completely alienated from political life joined it and took charge. There were times when it even felt like a revolutionary moment. It was, of course, no such thing, but it was perhaps a moment of insurgency. It was structurally, politically weak in that it had little purchase in social movements, and this weakness can account for why it fell away so rapidly.

Much, if not all of that energy and idealism has dissipated in the intervening decade, through a combination of burnout, British state suppression of democracy, and a failure of leadership, guts and imagination by the political class.

Almost all of the cast of 2014 have left the field. Nicola Sturgeon has announced she won’t be standing as an MSP for Holyrood next year; David Cameron hummed himself away from No. 10 after his Brexit debacle; Alex Salmond died last year; Alistair Darling died in 2023; the Queen is dead; Johann Lamont, who referred to Scottish Labour as a ‘branch office’ stood down in 2021; James Francis Murphy led Scottish Labour into the 2015 general election, in which he said, “I will not lose a single seat to the SNP” before the party lost 40 of its 41 seats during a landslide victory for the SNP, who won 56 of the 59 seats in Scotland; Blair McDougall is now an MP, and has just pledged his support to Labour’s plans to dismantle disability welfare.

In a peculiarly Scottish fashion, the winning side would clutch defeat from the jaws of victory with Labour suffering colossal reputational damage for the next decade for their involvement in Better Together, and the SNP would somehow manage to squander their historic Westminster victory of 2015 by being crushed in 2024 where Labour gained 36 seats from the SNP. In fact the SNP lost half a million votes, their share falling 15 percentage points to 30%. But, just to show the wild volatility of early 21C politics, Labour are now polling to lose badly in the Holyrood 2026 elections, while the SNP are, improbably, forecast to retain a majority.

What I’ve described above may not have been your experience of 2014. Maybe you were a No voter who just found the whole thing difficult and unbearable. But this was my experience and that of hundreds of thousands of others. But before we get too nostalgic, it’s worth noting that there were deep-seated problems within the Yes movement, problems that we can see much more clearly now in the rearview mirror of history.

The first problem is foundational. In order to achieve a moment of real change, a rupture, a break with the past and with the British state itself, massive structural forces would need to be in play. We had very few of these. We didn’t own the media, we didn’t have proper roots in the trade unions, and we had all of the most powerful interests ranged against us, including the British state (in all its forms).

The second problem was, and is, connected. The movement was unclear about its aims and values. Some of us viewed the task, the actual reason for the whole process to be ‘real change, a rupture, a break with the past and with the British state itself’, others didn’t. Some of the professional political class who tried to dominate the Yes movement, wanted to offset the real challenge of this and opted for a ‘don’t startle the horses’ approach. For some this was a tactical move that they believed was the right thing to do to win. Others opted for this tactic because they really didn’t want any kind of rupture. They wanted it to be like devolution, smooth, stately, safe and controlled and run by the establishment. The new Scotland they were imagining was pretty much the same as the Scotland we currently live in—but with them in charge. The flag would change above Edinburgh Castle but little else would really change. There would be no struggle with power, no shift in ownership or structural change.

Beneath this was a large section of the Yes movement that embraced this cautionary approach, not out of strategic awareness or cold calculation but because they were cowed, not very confident and had endured decades, or even centuries of being told ‘You don’t really exist’ and living in a culture that wasn’t recognised, valued or championed beyond tea towels celebrating tar macadam, Alexander Graham Bell or Rabbie Burns.

The Don’t Startle the Horses faction won (and lost). But these factions—or currents —fought side by side unconscious of the disabling differences until it was too late. The stultifying cry of ‘unity’ was used to suppress debate and understanding and to enforce the top-down managerial approach to movement building. Unity in diversity can indeed be a useful tool in political movements but not if it is used to champion a single lens or confuse genuine political differences. Arguably, the Yes movement was best when it was anarchic and insurgent, paradoxically when it was completely ‘out of control’. This gave the movement a feeling of energy, authenticity and complete difference from anything that people had experienced before.

The third problem was one experienced by the whole of society, but it proved a particular issue for the Yes movement. We live in digital silos, slave to the algorithm that often keeps us in bounded groups, literally talking to ourselves. At times, valiant efforts were made to change this dynamic and reach out and beyond, but this was hard, and made harder by the Unionist tendency to not engage, to cancel or not turn up for meetings. At times we were speaking into a void.

This was for good reasons. For some on the opposite side had literally nothing to say. Such was the low level of aspiration or critical thinking that the entire No campaign was reduced to ‘UK:OK’. This was the shortest slogan in the world and amounted to a disinterested shrug of the shoulders. It was the ‘Everything’s Fine’ when your house is on fire meme writ large. For anyone to look at the state of our world, our society, our country or our communities—and conclude that nothing really needs to change— seemed pretty grotesque—but accurately reflected the class demographics of the divide. So it wasn’t just the algorithms that kept us apart, it was also genuine, complete (and mutual) incomprehension.

Looking backwards, you can now see these fundamental problems with the independence movement that still remain with us today.

The brutal reality is that the landscape has changed so dramatically between 2014 and 2024 as to be barely recognisable as the same country. In 2014 genuine hope of change existed, political ideas were being tested and explored, new sections of society were engaged and animated and sections of the British establishment were sufficiently startled to rush to Edinburgh a few days before polling.

Project Fear

The No sides Project Fear was ultimately successful but it was also pitiful. The search for the ‘positive case for the Union’ was an unending one, and the arguments that Britain was either a) a progressive multicultural polity or b) a source of benevolent financial security now look absurd.

But even though the case for the Union was never made, and what arguments were made have been proven to be hollow or broken or lies, we remain in deadlock. The Yes movement is tired, burnt out and devoid of strategy. The SNP as the main vehicle for delivery is discredited and has shown little credible leadership towards independence.

It became a truism to say that ‘Scotland has changed forever’ after 2014, but that’s not really true. In reality, Scotland changed very little. We elected consecutive SNP governments, held a pro-independence majority at Holyrood, sent squad loads of MPs to Westminster, all to little effect. Scotland remains a country governed in social democratic centrist consensus, riddled with social conservatism, owned by landlords and landed power and now presided over by a tight network of lobbyists and a media-political class united in managerialism.

Yes the independence movement was deeply flawed and problematic and (probably) doomed; yes the SNP’s force and momentum lies in tatters; yes the independence has lost much of its hope, energy and drive. But for those indulging in triumphalism in this state of affairs, the wider picture is worth noting. The idea that Starmer’s Labour government is a unifying force, the idea that ‘Britain’ as a nation is a concept that can withstand the various forces allied against it: Welsh autonomy, Irish unification, Scottish independence, and most importantly English nationalism, seems outlandish. For those who repeat with some glee that the Labour government will never concede to a second independence referendum, it may be worth reflecting that simply holding 50% of a people in a state they have rejected isn’t a long-term solution.

The Hopium of the commentariat championed in endless op-eds has come to nothing. Writing in the Guardian in mid-March 2025 Nesrine Malik, author of ‘We Need New Stories’ writes[11]:

I reckon it’s time to call it. The threat to freeze personal independence payment (PIP) disability benefits shows that the fears voiced in the run-up to the general election were well founded. Keir Starmer’s government, cratering in the polls,[12] with Reform snapping at its heels, is in serious trouble. Weekend reports suggested the latest cuts are being reconsidered after a backlash from Labour’s own MPs,[13]charities and campaigners. It’s all vintage Labour, swinging between collected callousness and then flustered chaos.

Prior to the election, sceptics were told to keep the faith. Focus on the prize of getting the Tories out. It’s all three-dimensional chess, to whisper to rightwing voters. Starmer’s caution and inconsistency is only pragmatism, which could turn to radicalism in office.[14]

But you don’t hear that much anymore. The radicalism not only has not transpired, but something else, something cold and stomach-sinking, has emerged: a government clear in its intent on making savings by targeting the most vulnerable [15]in society—the sick, disabled people, mentally ill people. This isn’t simply a locking in of the austerity state Labour inherited, but an extension of it.

“I appreciate it must be so painful for the Conservative party watching a Labour Government doing the things they only ever talked about,” Wes Streeting told Tory MPs[16] this week.

Reducing the size of bloated state bureaucracy… bringing down the welfare bill. The public is asking ‘What is the point of the Conservative party?’

If that language seems familiar it is because it is the language of Britannia Unleashed spoken in the mouth of Labour’s Secretary of State for Health & Social Care. Labour’s tradition as a force for progressive and left politics is now little more than a folk memory.

Perpetual Collapse

If this feeling of constitutional inertia is both overwhelming and dispiriting it is added to by the wider frame of global upheaval: the chaos of Trump 2.0; the genocide in Gaza; the appeasement of Putin; the rise of the far-right; and the climate crisis, to name a few. The response to all of these disparate but connected features is the same: appeasement and complicity.

In a particularly British context, the much-vaunted ‘Neverendum’ is not for Scottish independence but for Brexit, which is an impulse never completed and never to be satisfied. This is because it was based on a mythology of past greatness and exceptionalism and on the idea that mysterious dark forces were holding Britain back from its true destination.

The challenge to overcome that rhetoric and the narrative that dominates much of British political discourse in print and broadcast media is a difficult but not insurmountable one. The challenge to overcome learned hopelessness is also not impossible. The story we are told and tell ourselves that the rise of these forces is both inevitable and spontaneous is wrong and disempowering. It requires us to overcome our reflexive impotence and design and create positive solutions for our collective liberation. The trick will have to be for us to live and not be altered ourselves in such a world, to curate our own stories and timelines and feeds, to bypass the propaganda and the scapegoat politics. The challenge is to survive in a world where everything is fluid: a world of QAnon and Neil Oliver and Canada under threat; and Wes Streeting and normalised destitution and corruption; and the relentless story that There Is No Alternative and ‘tough choices ahead’. Radical acts of self-care and conscious community building will need to go alongside entirely new political forms and systems and movements if we too are not to be permanently altered by the delirium and the breakdown. But these acts of self-preservation will have to be collective ones and will have to be aligned with efforts towards the creative disintegration of the British state.

Difford, Dylan. 2025. “How Do Gen Z Britons Think Their Own Lives Compare to Their Parents’?” Yougov.co.uk. YouGov. February 21, 2025. https://yougov.co.uk/society/articles/51660-how-do-gen-z-britons-think-their-own-lives-compare-to-their-parents. ↑

Ibid. ↑

Barnett, Anthony. 2024. ‘What Is Starmer’s Story?’ New Statesman. August 31, 2024. https://www.newstatesman.com/the-weekend-essay/2024/08/what-is-keir-starmers-story-england. ↑

Kwarteng, Kwasi, P Patel, Dominic Raab, Chris Skidmore, and Elizabeth Truss. 2016. Britannia Unchained. Springer. ↑

Cole, Mike. 2021. THERESA MAY, the HOSTILE ENVIRONMENT and PUBLIC PEDAGOGIES of HATE and THREAT : The Case for A… Future without Borders. S.L.: Routledge. ↑

2025. X (Formerly Twitter). 2025. https://x.com/YesScot/status/1464922577466449929. ↑

‘Diagonalism, the Cosmic Right and the Conspiracy Smoothie.’ 2024. Bella Caledonia. June 26, 2024. https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2024/06/26/diagonalism-the-cosmic-right-and-the-conspiracy-smoothie/. ↑

Rhoden-Paul, Andre. 2023. “Penny Mordaunt’s Sword-Wielding Role – and Other Top Coronation Moments.” BBC News, May 6, 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-65510506. ↑

Nairn, Tom. 2001. After Britain : New Labour and the Return of Scotland. London: Granta Books.

↑

Labour. 2022. “Section 3 · Chapter 12: Conclusion and next Steps Information about the Commission Acknowledgements.” https://labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Commission-on-the-UKs-Future.pdf. ↑

Malik, Nesrine. 2025. ‘Many Said the Starmer Era Would Be Just Tory-Lite – Now It’s Worse than That. Time to Stop the Pretence.’ The Guardian. The Guardian. March 17, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/mar/17/keir-starmer-tory-radical-prime-minister-poor-people.

YouGov. 2025. ‘Voting Intention: Lab 24%, Ref 23%, Con 22% (9-10 Mar 2025).’ Yougov.co.uk. YouGov. March 11, 2025. https://yougov.co.uk/politics/articles/51767-voting-intention-lab-24-ref-23-con-22-09-10-mar-2025. ↑

Helm, Toby, and James Tapper. 2025. ‘Downing Street Considers U-Turn on Cuts to Benefits for Disabled People.’ The Guardian. The Guardian. March 15, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/mar/15/downing-street-considers-u-turn-on-cuts-to-benefits-for-disabled-people. ↑

Hayward, Freddie. 2023. ‘Labour’s Caution Could Turn to Radicalism in Office.’ New Statesman. August 16, 2023. https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk-politics/2023/08/labours-caution-could-turn-to-radicalism-in-office. ↑

Editorial. 2025. ‘The Guardian View on Labour’s Welfare Plans: Betraying the Vulnerable.’ The Guardian. The Guardian. March 12, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/mar/12/the-guardian-view-on-labours-welfare-plans-betraying-the-vulnerable. ↑

2025. X (Formerly Twitter). 2025. https://x.com/breeallegretti/status/1900157819132711190. ↑